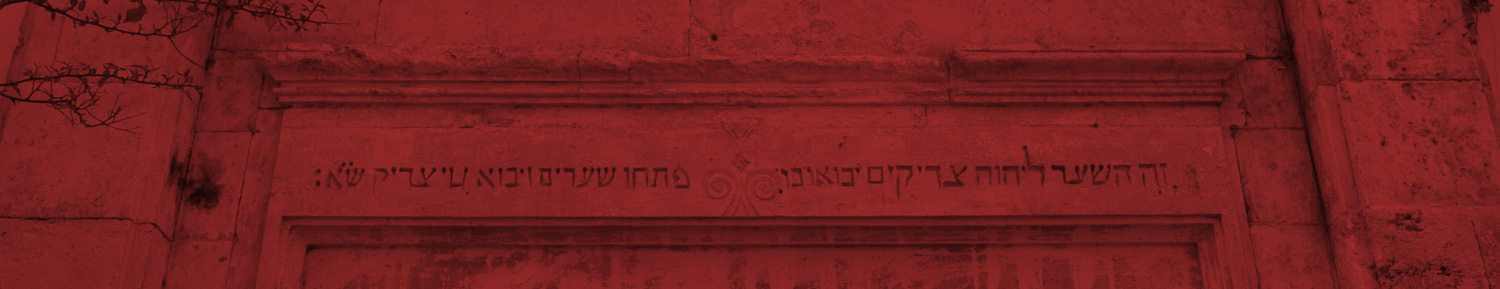

The Rothchild Gate

Etz Hayyim Synagogue is accessed through the Rothschild Gate, its pediment featuring a turquoise plaque bearing the modern seal of Etz Hayyim Synagogue framed by the word “Peace” in Greek and Hebrew. This plaque, designed by Nikos Stavroulakis, replaced an older dedication that had not been found at the time of the synagogue’s restoration when the pediment was reassembled from pieces recovered within the filling material in one of the synagogue windows. There are also two original Hebrew inscriptions on the gate. Abraham Evlagon, the last Chief Rabbi of Crete (1846-1933), mentioned the gate in his efforts to raise money for its reconstruction in 1900 following considerable damage caused by an earthquake. Those funds were eventually provided by Baron Albert Rothschild of Vienna and the gate was thus named the “Rothschild Gate.” At the northern end of the courtyard, the original doors of the Rothschild Gate are displayed as they were found at the time of the synagogue’s renovation by Nikos Stavroulakis.

.

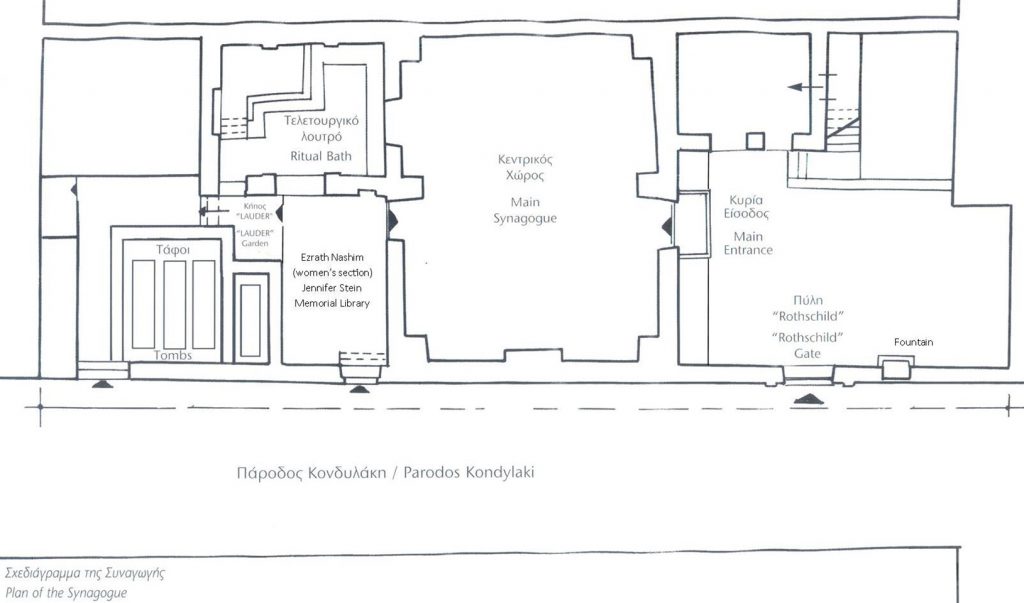

The Northern Courtyard

Visitors enter the northern courtyard (and the synagogue complex as a whole) through the Rothschild Gate which functions as a forecourt for the synagogue sanctuary. The entire surface of the courtyard is covered by a pebble mosaic pavement that was discovered by Nikos Stavroulakis under a layer of cement overlying a protective stratum of sand laid by the squatters in the mid-1940s-1950s. This pebble pavement most likely dates to the 15th or 16th centuries and is visibly flattened in areas from all of the foot traffic of community members and other visitors entering the synagogue from the Rothschild Gate over a long period of time.

.

A small stone fountain is set in the east wall of the northern courtyard. It replaced the original one that had been broken apart by squatters after the Second World War. The stone frame of the fountain is constructed from carved fragments of lintel stones discovered in the roof of the synagogue when it was removed during the renovation. The fountain is used for the washing of hands with a netilat yadayim (ritual cup) before prayer. To the right of the fountain, a plaque commemorates the main donors who contributed towards the reconstruction of Etz Hayyim Synagogue.

.

On the west side of the courtyard stands a small building with an external stone stairway leading to an upper floor. This building was probably added to the synagogue complex in the 19th century to provide an additional upstairs women’s gallery. Women would have followed the service in the main sanctuary from this vantage point. Today, this space is used as both a library and exhibition space. The ground floor originally served as the lodge of the shamash (caretaker), but presently functions as the main synagogue office.

.

The Synagogue Sanctuary

The main entrance to the sanctuary is located at its north wall. This entrance is positioned directly opposite another door on the south side that leads to the main women’s gallery, as well as the Mikveh and southern courtyard. The framing stones of the sanctuary entrance and the overlying lintel appear to vary in workmanship and therefore, the lintel may have originated from an older building. Unfortunately, the entrance gate was fitted with an electric fixture that damaged part of the still visible inscription on the lintel at the time when the synagogue was occupied by squatters.

.

The interior of the sanctuary is laid out according to the tradition of Romaniote Jewish communities in Greece. Several examples have survived today, most notably in Ioannina, Halkis, and Corfu and what remains of the interior furnishings of the synagogue of Patras. This layout differs from that of Sephardi synagogues in Greece and can also be found in Venice, elsewhere in Italy, and occasionally in Turkey and North Africa. In keeping with all synagogues, the Ehal is located on the east wall, but the Bema is positioned axially opposite on the sanctuary’s west wall which is typical of Greek Romaniote synagogues. The seating arrangement follows this polar-axial layout so that the benches are either situated against the south and north walls of the sanctuary or along the central aisle. It is a highly practical solution to the problem of processions where the congregation must follow the Torah as it is brought from the Ehal to the Bema and back again, or even the interior circuits that are performed at certain festivals such as Sukkoth. From the position where the congregation is sitting or standing, as such, an individual can easily face east or west at the same time as reaching out to touch the Torah.

.

The Ehal contains the Torah scrolls of the synagogue and is usually always located on the east wall facing the direction of Jerusalem. At Etz Hayyim, the original Ehal was lost when the synagogue was looted following the arrest of the community in 1944. However, the approximate measurements and position of the Ehal were rediscovered during the synagogue’s restoration in the mid-1990s. Several socket holes of the original shrine where uncovered, as well as evidence of the existence of a tribune that had separated it from the congregation. The Ehal is positioned on the east wall beneath two arched windows. It comprises a large teak cabinet placed on its head with ornately carved legs and fitted with a handmade parohet (curtain). Above the Ehal is a carved wooden tablet of the Ten Commandments that are represented by the first ten letters of the Hebrew alphabet equalling the numbers one to ten. Inside the Ehal are two Torah scrolls: an Egyptian Torah from Cairo that was a personal gift to Nikos Stavroulakis and another scroll from Eastern Europe on loan from the London-based Memorial Scrolls Trust.

.

As in every synagogue, a Ner Tamid (eternal light) is hung above the tribune in front of the Ehal at Etz Hayyim. The Ner Tamid consists of an original Venetian glass lamp suspended within a finely-made bronze Magen David (Star of David) with six amber pendants. It is commonly associated with the Menorah, the seven-branched lamp, together with the continuously burning incense altar inside the Temple in Jerusalem. It is viewed as a symbol of G-d’s eternal and imminent presence within the community.

.

The Bima is an elevated platform from where the Torah is read during services and forms an important part of a synagogue’s interior. In Ashkenazi and Sephardi traditions, the Bima is commonly positioned either in the centre of the synagogue or immediately in the front of the Ehal. However, in the case of Etz Hayyim and other Greek synagogues, the Bima is placed axially opposite to the Ehal against the west wall, thereby conforming to the local Romaniote tradition. As in the case of the Ehal, at the time of the synagogue’s renovation, socket holes were identified on the west wall indicating the approximate measurements and location of the original Bima. The present Bima was designed by Nikos Stavroulakis and inspired by Bimas in other Greek Romaniote synagogues.

Traditionally, men and women are separated during prayers in a synagogue. Men pray in the main sanctuary, while women attend prayers from a separate area called the Ezrath Nashim (women’s gallery). Today at Etz Hayyim, all community members sit together during prayers in the main sanctuary. The two second-floor women’s galleries are now used as offices, as well as library and exhibition spaces. The original primary Ezrath Nashim at Etz Hayyim Synagogue was a two-story wooden domed structure attached the south-east façade of the main sanctuary. It provided visual access to the interior of the synagogue for the women through a lattice-work screen in the south-east gothic arch. This structure was destroyed during the German bombing of Hania in 1941. All that remained of this original Ezrath Nashim at the time of the synagogue’s restoration were some support beams and wooden floorboards that were found around the southern entrance of the sanctuary. In 2008, this women’s gallery was rebuilt as the Jennifer Stein Memorial Library. A second women’s gallery had been added in the 19th century on the second floor of the caretaker’s lodge in the northern courtyard.

.

A memorial to the members of the Cretan Jewish community who perished during the Shoah can be found immediately outside the door in the sanctuary’s south wall that leads to the main women’s gallery and the Mikveh. The names of the victims are listed on bronze plaques. This memorial was the only one to the Cretan Jewish victims of the Shoah until the inauguration of a municipal monument in October 2013.