The southern Ronald Lauder courtyard to the south of the synagogue sanctuary contains four graves of former rabbis of the Hania community which are mentioned by Crete’s last Chief Rabbi, Abraham Evlagon (1848-1933) in his memoir published in 1921. Here, he gives the precise names and dates of Rabbi Joseph Ben Shalom (d. 1821) and his brother, Rabbi Baruh Ben Shalom (d. 1841). There is also a grave of Rabbi Avraham Z. Habib of Gallipoli, who died in 1858, and a fourth grave of Rabbi Hillel Eskenazi, a noted mystic and kabbalist, who died in 1710. Evlagon also notes that this last burial was recorded only in tradition and that its original location had been lost. In the course of removing rubble and the paving stones of the ground floor of the women’s gallery during the synagogue’s reconstruction, a tomb was brought to light under the stone stairs that had been incorporated into the support wall. This is undoubtedly the tomb of Rabbi Hillel which was not visible when Evlagon wrote his memoir. The close association of the tombs of the Shalom brothers is explained by Evlagon. Before Rabbi Baruh Shalom had died, he requested that he be buried by the side of his brother. Apparently, Rabbi Joseph Ben Shalom was buried twenty years earlier within the walls of Hania, contrary to Jewish religious law, after what Evlagon describes as a “scandalous affair” that forced the Jews to barricade themselves behind the gates of the Jewish quarter for several days. This development was probably due to considerable social unrest at the beginning of the Greek Revolution in 1821 on the Greek mainland. The graves are enclosed by an Eruv (border or delineation) separating the small burial site from the synagogue because Jewish law dictates that graves must not be positioned in close proximity to the sanctuary and Mikveh.

.

Dominating the east wall of the courtyard is a large white-washed ossuary containing the bones of fifteen Jews who had passed away during the German Occupation. This ossuary cotains some special mortal remains:

.

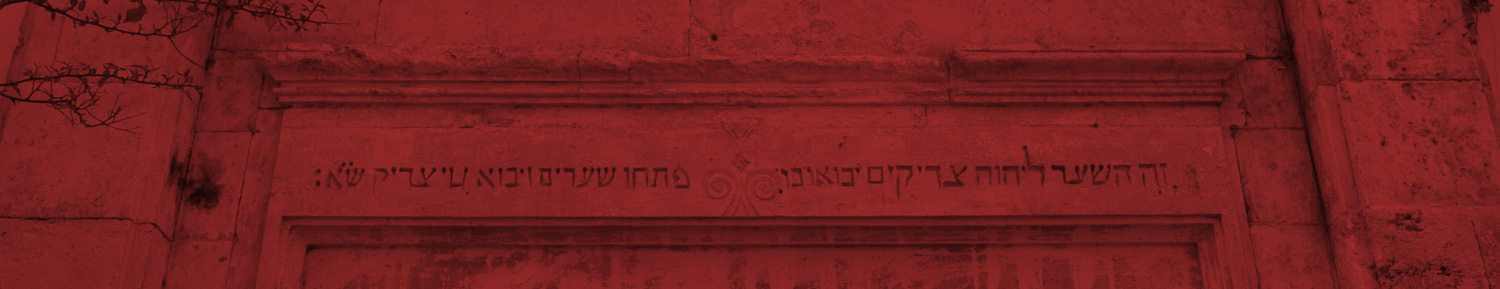

In 2009, Nikos Stavroulakis, the then-Director of Etz Hayyim, was called upon by the Archaeological Authority in Hania to identify some skeletal remains found in the vicinity of the former Jewish cemetery which, prior to the Second World War, was situated to the west of the old town of Hania in the modern Nea Chora district on a plot of land extending southwards from the sea shore for a distance of about 200 metres. In his memoir, Evlagon described the cemetery being open on all sides until 1900 when it was enclosed by a perimeter wall with financial assistance of the then Chief Rabbi of France. During the German Occupation, the cemetery was largely destroyed. Sixty-five years later, Nikos was able to establish with a high degree of certainty that the skeletal remains most likely originated from in situ Jewish burials on the site of the former cemetery. The absence of any names on the large flat stones covering the burials suggested to him that they dated to the period of the German Occupation of Hania (1941-1944) when it would have been impossible to inscribe the tombstones in Hebrew. In the end, it was decided that these skeletal remains stay in Hania and a solution was found in recourse to the ancient Jewish practice of family sarcophagi that lasted well into Hellenistic times. On the ossuary, a copy of a gilt-glass Hellenistic Jewish seal – with a depiction of the Temple and a menorah based on an original found in the Jewish catacombs of Rome – was placed along with a plaque with verses taken from Ezekiel in Hebrew, Greek and English which reads: “I will put my breath to enter into you and you shall live again. I will lay sinews upon you and cover you with flesh and form skin over you. And I will put breath into you and you shall live again, and you shall know that I am the Lord.” Along the walls of the southern courtyard are some tomb stones inscribed in Hebrew that were recovered from the site of the old Jewish cemetery where a school was later built in the 1960s.